Driving / Technique

In order to drive fast, we must stay on the limit of the vehicle's performance. Achieving this limit is complex, but rewarding. In this post we will look through each aspect of achieving the limit from a driving technique point of view so you can refine your skills and get faster, faster!

Slip Angle

What is slip?

A tire's contant patch (the part that touches the ground at any given moment) twists and smears as the tire generates forces. To get an idea of how this might look when a car turns through a corner, push the tips of two fingers from your right hand into your left palm and twist. The amount of twisting that occurs is known as slip angle and it is necessary in order to generate lateral (cornering) grip.

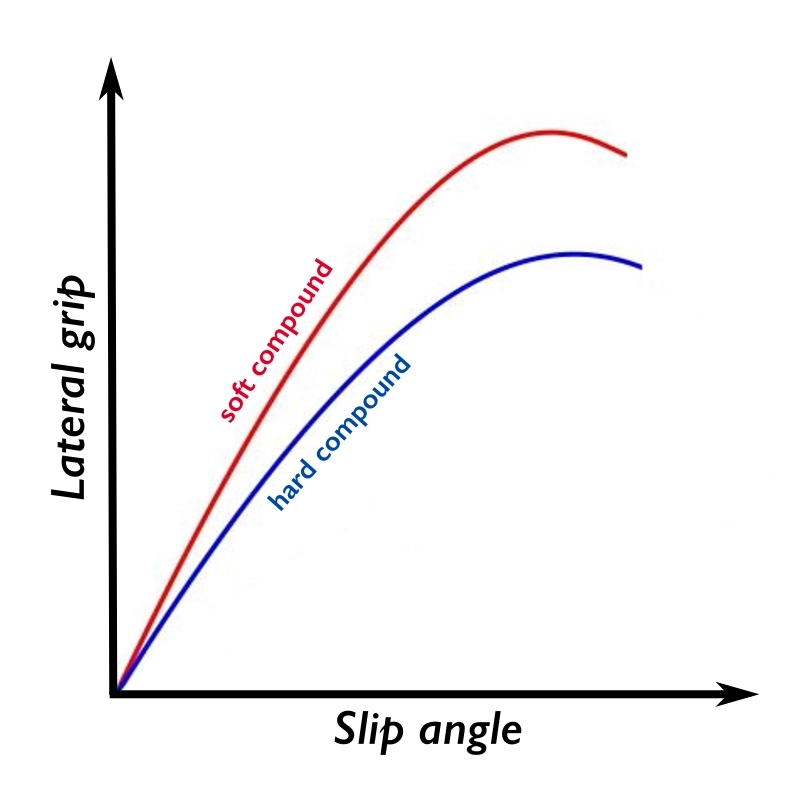

The more lateral grip a tire produces, the greater the slip angle of the tires, at least until the tire is overworked, after which point the amount of grip begins to reduce. Every type of tire has an optimal slip angle and it is a driver's duty to maintain this optimal slip throughout a corner.

Some tires may plateau for a bit before falling off in performance in which case a driver should aim for the start of the plateau, that is, the lowest slip angle that still generates maximum grip; slip in itself produces drag and wear, so while we use slip in order to obtain grip, once we plateau in performance we don't want to introduce any more slip. That said, if a track is cold or the tires are too hard and they have difficulty warming up, intentionally over-driving into greater angles of slip can be a valid tradeoff in order to build optimal tire temperatures.

Importantly, the driver can feel this affect in their steering wheel. As the grip of the tires increase, so too does the weight of the steering wheel. However, the relationship is not one-to-one; the steering weight will peak before we reach the top of the lateral grip curve and will then begin to dip slightly from there as we approach grip maximum. Thus, when the driver is looking for peak grip, they are actually looking to push slightly past the heaviest part of the steering wheel feedback. Exactly how far depends on the tires and vehicle speed, so it can't be easily presumed ahead of getting familiar with the car. Instead, the driver will need to drive slightly past the grip limit and get a sense for how far past the max steering weight they need to go in order to be at the maximum grip of the tires. Once done, the level steering weight will be an important cue to the driver as to whether they are pushing the car too much or too little as they steer through a corner.

Slip and slide

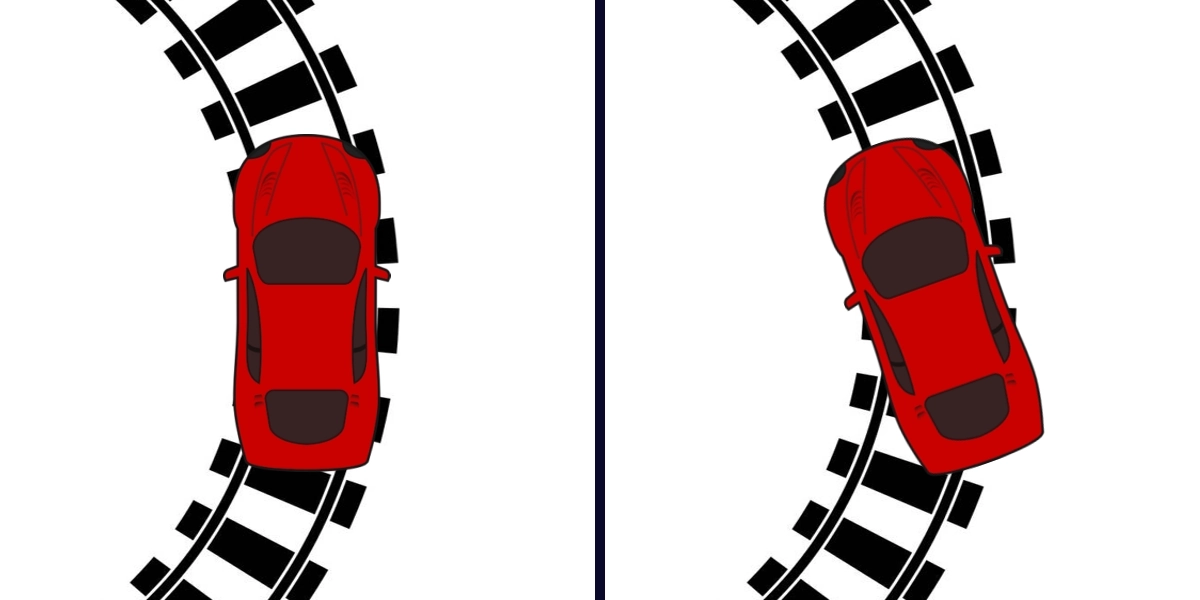

Due to slip angle effects, driving through a corner at the optimal slip angle will feel like the car is sliding. This doesn't mean the car is drifting where the back end is squealing across the road and the driver is balancing with counter steer, it simply means that the car seems to be cocked slightly into the turn more than one would expect if driving "on rails" like a train on tracks.

If the driver is not sliding the tires at all, they are driving too slow. If they are sliding, then they are finding the limit, but if they are sliding too much, they are scrubbing off speed. Most new drivers drive without sliding at all, as if they are on rails. They must learn to slide the tires more and more, getting faster and faster, until they begin scrubbing off speed, after which they should bring things back to optimum.

Much of the feeling of slip angle comes through a driver's vision. Look as far ahead as you can through the corner so you can get a sense of how your car's trajectory compares to your body position. The car should feel like it is slightly nosed in, and with enough practice you can get a sense of how much this should be the case before you start scrubbing off speed.

The best way to get into this state is to initiate the slide from the very start of corner entry and then control it throughout. This is a much more calm and relaxed way of learning than starting off a corner well under the limit and then trying to creep up on the slide without accidentally going too far over and potentially losing control. As well, this approach is ideal because we will be practicing in exactly the way we wish to perform; sliding from the start is the fastest method since it maximizes slip angle as much as possible throughout the corner.

Settle down

In the middle of the corner, after corner entry but before corner exit, the vehicle should be fully leaned over and settled. This is known as "taking a set". As well, the phase leading up to this point should be a smooth transition into this settled state. Our goal is to get the car to set as fast as possible, without throwing it around and causing too much initial weight transfer.

Choppy, tentative steering inputs will keep the car from transferring smoothly from braking to cornering. Aggressive, sudden inputs will cause the vehicle's weight transfer to spike and fall, only to have to rise again as we progress toward the apex. If you were properly on the limit before turn-in, this spike in weight transfer will send the car well over the limit, forcing you to save a spin or manage a load of understeer, both of which waste time and speed. Or, if neither of these happen, you were underdriving to begin with and the aggressive turn-in is a compensation technique to get the vehicle to suddenly come to the proper slip angle.

Smooth, assertive, confident steering and pedal inputs will allow car to smoothly roll around the edge of the traction circle and settle into its optimal cornering attitude.

Averaging on the limit

The idea

Don’t try to drive right up to the limit without going over, you will just drive consistently under. This would be like trying to balance on a tightrope that is placed up against a wall. Balance implies making subtle corrections in both directions; if you're only able to lean in one direction you'll never be able to actively balance.

Instead, the goal is to try to drive right on the limit, happily playing equally over and under. You should be able to overdrive a car (in a controlled manner without getting caught out) and bring it back. With that said, you don’t have to spin the car to know the limit. That would be analogous to falling off a tightrope on purpose to learn to balance; you’ll learn by successfully playing on both sides of the limit, not by throwing yourself so far over it becomes irrecoverable.

As your skill increases, deviations over and under the limit will become smaller and smaller. You’ll never be a perfect driver; you’re always making mistakes, perhaps multiple per corner, but over time you will become very good at minimizing them. The best drivers recognize mistakes sooner and correct them with more subtlety before they become larger and require more dramatic corrections.

Ultimately, good car control (being able to slide the car from turn-in and through the corner, balancing over/under/over the limit) is what enables a driver to go fast. And don’t fight the car to get the behavior you want; being smooth is more important than trying to be fast. Speed builds upon smoothness, so if you want to “push” yourself to go faster, do it by pushing yourself to drive smoother.

The approach

So far, discussion about balancing the car on "the limit" has seemed to imply a single dimension, but there are actually two continuums across which we are trying to balance at the same time: the grip limit and the oversteer/understeer balance. The grip limit is whether we are overdriving or underdriving the vehicle; this is managed primarily with the steering wheel. The balance is whether we are balancing the car so as to have oversteer or understeer; this is primarily managed with the pedals.

If we are turning the steering wheel too much, beyond what the car can handle for its current speed, we are overdriving the vehicle. Whether the result is oversteer or understeer depends on the vehicle's balance, but the steering wheel cannot help rebalance us along that continuum. If we are turning the steering wheel too little such that the car is not threatening to oversteer or understeer, then we are underdriving the vehicle.

When the vehicle does inevitably go (slightly!) over the limit of grip, its balance will determine how it reacts. At the same time that we will be managing our steering input to bring the car back from being over the grip limit, we will also need to pay attention to its rotation in order to manage its balance. If the vehicle begins to over-rotate, past the optimal slip angle, we will need to use our pedal input to move us toward understeer. On the other hand, if the vehicle does not rotate at all when being overdriven, we will need to use our pedals to subtly move us toward oversteer. The goal is neither oversteer nor understeer, but to balance in between the two, which, like balancing on a tightrope, requires us to be able to intentionally move toward one as we accidentally find ourselves falling toward the other.

The execution

So what does it look like to actually implement the strategy above as a driver? Each phase of the corner is slightly different, so let's go through them one at a time.

Corner entry

Given that drivers prefer to lock a front wheel rather than a rear, their brake bias will generally impart understeer throughout the entry phase. As such, the rest of setup will tend toward oversteer during this phase to balance out the understeer induced from trail braking. This means that, at any given moment while trailing off the brakes, more braking would hold on to some understeer, and less would release understeer and allow for more oversteer.

With this in mind, the driver will balance the car as follows,

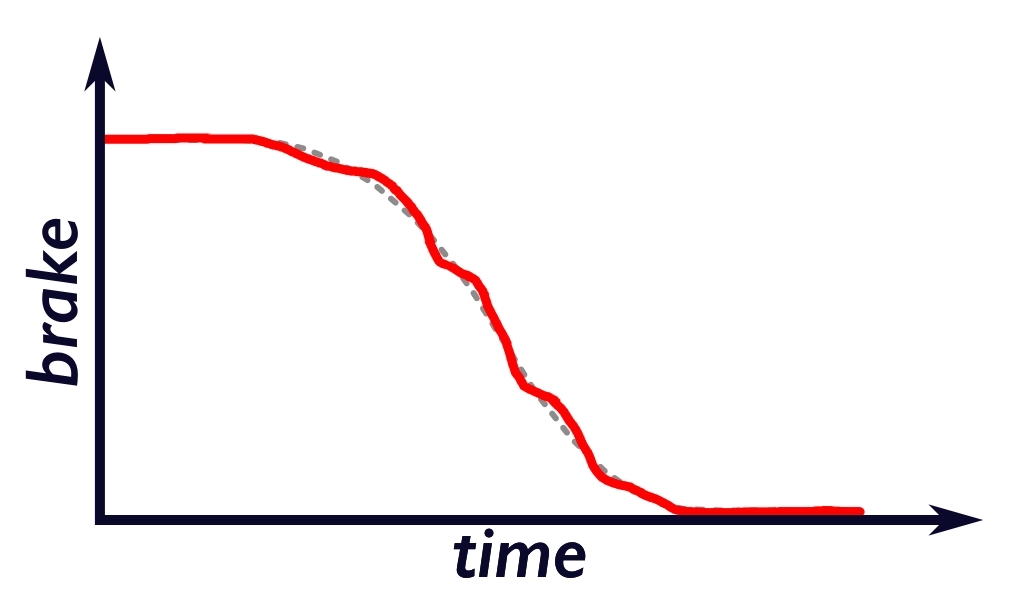

- If oversteering: The driver should slow brake release to induce some understeer for the next moment.

- If understeering: The driver should quicken brake release to induce some oversteer for the next moment.

- All the while, the driver will be adding as much steering as they can to follow the grip limit, slowing their input if they start to notice overdriving (oversteer or understeer), or quickening their steering input if they notice no overdriving.

The driver's brake trace will have "stair stepping" as they trail off the brakes at changing rates, but ideally will always be reducing, never coming back up past the previous point. Likewise, the driver's steering input should always be moving into the turn, quickening or slowing as they keep up with the grip limit's ever changing position (as the driver rides the brakes into the corner, the ever-slowing vehicle can thus turn on a tighter and tighter radius), but ideally never stopping or reversing direction.

Of course, managing the vehicle is the ultimate goal and a driver should not force themselves to drive to an ideal that isn't achievable at that moment; forcing oneself to an ideal instead of dealing with large mistakes as they come (ie. choosing not to countersteer when the car begins to spin) will only end it disaster. Deviating from the ideal generally implies a mistake was made in the moments leading up to that point. Non-ideal driving inputs should be a signal that the driver's technique earlier in the corner needs improvement the next time around.

Mid-corner

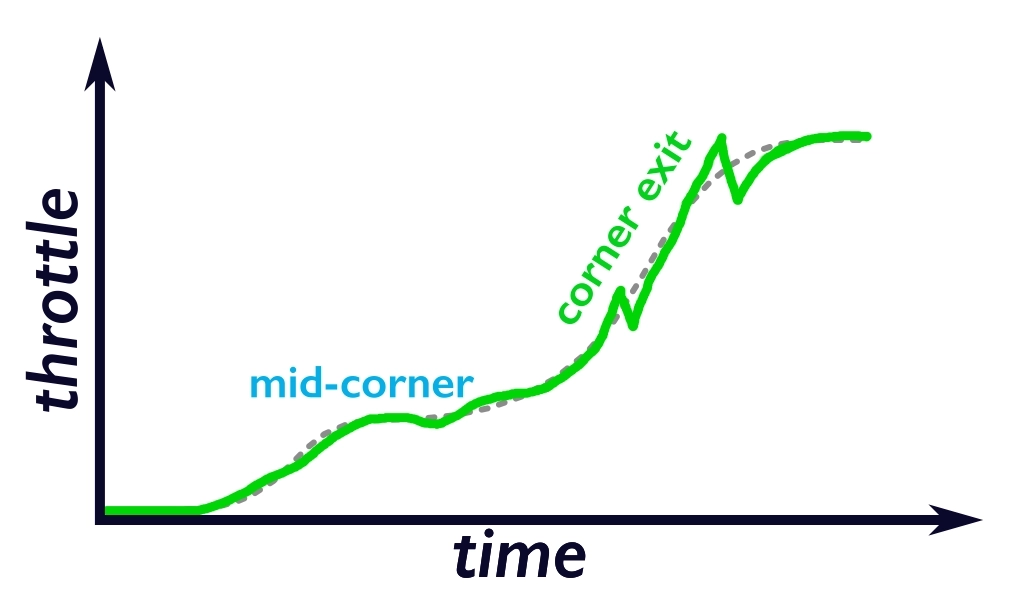

During the mid-corner phase the driver will be maintaining a constant level of "maintenance throttle" with the goal of maintaining a constant speed and steering input as they cut an arc of constant radius through the middle of the corner, clipping the apex as they go.

If the vehicle has a lot of front-to-back weight transfer, slight accelerations (squeezing on a little more throttle input) will pitch weight back onto the rear tires whereas slight decelerations (lifting off a little bit of throttle input) will tip weight forward onto the front tires.

With this being the case, the driver will balance the car as follows,

- If oversteering: The driver will add a little more throttle to provide more grip to the rear tires.

- If understeering: The driver will lift off the throttle slightly to provide more grip to the front tires.

- At all times the driver will hold the steering wheel nearly steady into the turn with only small deviations in either direction to make sure they stay neither too far over or too far under the limit of grip.

Corner exit

During the corner exit phase the driver is removing steering input while adding throttle input. But in terms of balancing the vehicle, the dynamics are the same as the mid-corner: adding throttle more quickly than the ideal will induce some understeer and adding throttle more slowly will induce oversteer.

That said, while a little extra throttle will add grip to the rears, inducing understeer, far too much throttle will cause the vehicle to power oversteer. As seen in the figure above, the only way to react is to drop throttle quite significantly so that the vehicle does not spin out. Suddenly reducing the steering could also save the spin, but may send us off the outside edge of the track. It is important that mistakes here are minimized so that our exit speed does not suffer from having to lift off the throttle.

Full and round

In practice, there are many trajectories a driver can take through a corner. There is the ideal line, assuming a car with perfect balance and well-rounded capabilities. However, some vehicles tend to rotate better during the first half of the corner or the second half, some vehicles have lots of power and thus can take a more V-shaped trajectory mid-corner to allow for a straighter, more powerful exit, and some vehicles have very little power and need to extend their mid-corner to be as long and fast as possible.

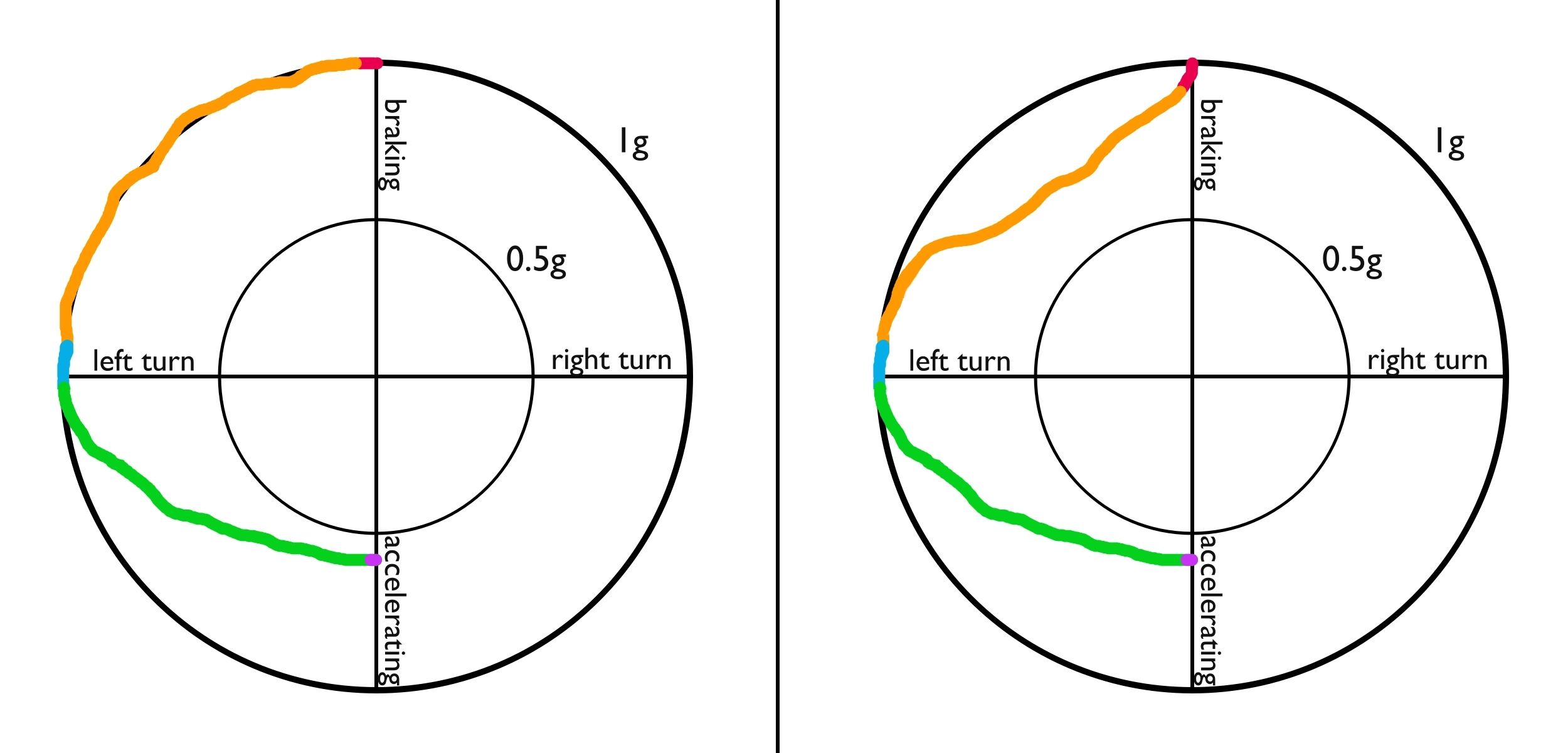

However, no matter the trajectory taken, every driver is trying to maximize the g-g circle, riding the rim of the maximum performance envelope at all times. They may linger in certain parts of the outside rim longer than others depending on the shape of their chosen trajectory, but they should never wander inside the envelope, as this would indicate underdriving (not using the tires as much as possible), or overdriving (which scrubs off speed).

While staring at a g-g diagram while cornering is possible, it is not advised. Instead, the driver should be paying careful attention to the weight in their steering wheel and the behavior of the vehicle. If at any point it feels as if the driver could turn the wheel more without the car scrubbing or spinning, then they should have carried more speed into the corner. In this case, the g-g diagram would have a flat spot somewhere. On the other hand, if they can't manage to make the apex of the corner, then they carried in too much speed. In this case the g-g diagram will look filled-out, but the driving line would be sub-optimal and their exit trajectory would suffer.

As well, if at any point the driver is afraid to turn the steering wheel even slightly more, the car is probably too oversteer at that part of the corner. More performance can be found by adjusting either technique or setup.

Finally, be sure to maximize the performance of the vehicle throughout 100% of the lap. This may sound obvious, but there are many places where a driver may simply coast, waiting for their next move. This often happens in the middle of chicanes where even a short squeeze of the throttle would be faster but isn't done because the driver feels it's too short to make a difference. Every section of the track counts and leaving any performance on the table, lap after lap, can change the outcome of the race. Always attack the track! You aren't reacting to each section of the track as it comes, you're attacking the section you're on.

Tips and Tricks

Find speed by adjusting turn-in

A driver that wants to carry more speed into a corner should do so by focusing on altering their turn-in location and speed, not by trying to brake later. Although braking later is a natural consequence of trying to turn in with more speed, focusing on braking later usually results in harder braking (which could lock a wheel) and little to no change in actual turn-in. Instead, when entering the braking zone, focus on delaying turn-in or carrying more speed at the same turn-in a small amount each time until the corner comes together. After you find the right turn-in location and speed, the desire to brake later to match will come naturally.

Use reference points

Feeling your way through a corner isn't bad per se, but to consistently go as fast as possible, you need to find and use your own reference points. As your familiarity with each corner increases, the references will be used more subconsciously, but they must be identified and tracked consciously to begin with.

Corrections good, reactions bad

A driver should never pretend they are perfect; making corrections is not admitting defeat, it's doing the dance, actively finding the limit. However, there is a difference between correcting your balance and reacting to the consequences of harsh overdriving. You shouldn't be surprised by any of the vehicles behaviors so as to need to make reactive saves. If you do find yourself constantly reacting to unforeseen car behaviors, there is a disconnect between you and the vehicle. This could either be an aspect of your technique, a poor setup, or a misunderstanding of the vehicle's natural tedendencies causing you to fight it instead of working with it.

That said, if you do need to make a save, your steering input should be fast and large. A slow, smooth attempt at a save will usually not be enough to prevent you from spinning; the vehicle will already be too far gone and past the point of no return. But, do not hold your saving reaction and wait for the car to straighten out as this will only send it spinning in the opposite direction. Make a large, saving input, notice the over-rotation begin to slow, and then quickly return your steering to the optimal angle, as if anticipating that the save will work before it fully does so.